This blog is retired now, but charts some of the final months in the job that I resigned from at the start of ANARCHIST ATHEIST PUNK ROCK TEACHER.

1 in 3 UK teachers are considering leaving the profession in the next five years. I’m currently one of them. This is a blog to reflect on my day to day struggle between personal wellbeing and being a teacher.

End of Term 2021

“Finally…the year that would not die has died...”

Finally…the year that would not die has died.

I remember last September. Having spent an incredibly safe 2020 lockdown mainly in my own garden, venturing out only for the odd walk in a well-distanced National Trust property with my wife, or that one time I got a new tattoo, we had resigned ourselves to re-entering the world despite no change in the danger-levels and faced the new term at peace with the fact of its awfulness. Lessons would have to be delivered differently, the way we engaged with colleagues would be altered - it would all be very weird. But after six months away from school we were as ready as we could be for the weirdness. After all - we’d been sent details of all the safety measures which would apparently protect us from this world-changing virus at work. Hand sanitiser. Masks. Bubbles. It would become the new language of the classroom, rolling easily off our tongues in the weeks and months to come. It would ward off the coronavirus as effectively as any empty spell based on fantasy rather than science.

I knew that too - that it was all doomed to fail. I had written about it extensively in the months before on my Philosophy Unleashed blog and on Twitter. How “bubbles” weren’t bubbles. How we needed good ventilation, not hand sanitiser. How masks needed to be worn in the classroom and not just the corridors - and especially worn by the teacher who was speaking not, perversely, taken off precisely by those projecting their spit and spray out into the air the most (as quickly seemed to become common practice). I found it hard to believe a profession supposedly dedicated to education and learning could buy so completely into these empty appearances of safety instead of basing safety measures on the real science of epidemiology…but I already knew that going in. My eyes were open. I assumed disaster would ensue and was only really surprised it took as long as New Year for the second full lockdown to take place.

September to December was tough. It quickly became apparent even the illusion of safety measures weren’t being followed by everyone at school, or the reasons for them even understood. I felt very isolated and alone for simply asking others to do what was needed to keep us all as safe as possible. Staff and students. There was none of the old camaraderie of the staffroom. I barely spoke to fellow colleagues as my school decided that rather than enforce its own safety measures properly so that all staff would be safe, it would just stick me in a room to work and eat by myself where I couldn’t complain too loudly. Students too, treated the measures with hostility, making every lesson at the beginning a battle of expectations and behaviour instead of a fun learning experience. Meanwhile every lesson had to be revamped for the new Covid-classroom anyway. All our group work, shared resources, etc. had to be thrown out as pupils were sat in straight rows facing the front and unable to interact with each other or us.

In an effort to minimise contact with potentially contaminated surfaces, we tried to get to grips with a “paperless” approach where possible and “enjoyed” all the associated tech difficulties that came with it. It was difficult trying to speak for six period days through a mask so that students could hear and my throat could survive, but we had also lost our classroom spaces and become nomads wandering from room to room across the school, going to our class groups each lesson instead of them coming to us. I felt un-anchored. Adrift. Unhappy.

Then groups suddenly started being pulled out of school to self-isolate for weeks at a time and the hybrid approach of teaching some students in-school and others at home began in full gusto. You never knew what each day would bring.

When that first half-term ended and we reached the holiday that had seemed so impossibly far away in September, where it was finally time to de-stress and feel safe again, we got an email the first Sunday of our break telling us our boss had died. Heart attack. No warning. Friday he was talking to us about strategic planning for the years ahead, Sunday he was dead. Instead of a relaxing and revitalising holiday, I mourned and struggled with a conflicting range of feelings about a man who was both friend and foe. We returned to school and tried to come together in grief at a time when we couldn’t come together. I bristled as protections went out the window so we could do, in school, what no one else in the country was allowed to do at a funeral. The staffroom filled. There were hugs and tears. I stayed away, backing further into my isolation. Alone with my grief.

As cases began to spike, behaviours got sloppier. We were rudderless and doing what was needed to feel ok…but more and more kids had to self-isolate and the rest of the country (just not the schools) shut down in a “circuit breaker” mini-lockdown. Instead of shutting down at school, however, we did a mammoth session of exams. Mocks for the year 11s and 13s. Endless piles of marking. Parents Evenings online. Cold classrooms with windows and doors open despite the frost. Miserable memories of a horrible time.

Getting Covid that Christmas was the icing on the cake. The slow-moving car crash I could see but not stop. The unwanted inevitable. I kept hearing the words of AEW wrestler, Taz, taking a shot at WWE after a Covid outbreak there during the summer while AEW remained clean: “we don’t run a sloppy shop”. Our shop had got way too sloppy…and now I had brought the dreaded plague we had been successfully avoiding all year home with me, ruining Christmas and putting not only my own, but my wife’s life, at risk.

When the lockdown came in January, I was happy. Bluntly, I wasn’t intending on returning until school felt safe again and had written an email explaining my position a day or two before the point became moot and government inaction turned to badly timed action. I had flourished during the previous lockdown, and my department’s online learning provision was excellent. But this one felt far more stressful than before, and not simply because it took weeks for the Covid to leave my system. Instead of the flexibility we’d had before, 2021 online learning foolishly attempted to mimic the school day, so we were staring at screens for hours instead of being able to set appropriate levels of work for the different context. Scratchy eyed days of talking into the void - both of the blank screen staring back at us and the void of expectations wrapped up in the pretence of having too many of them. By starting September with the general consensus that all online learning done in 2020 had been a waste of time, students had suffered “lost learning” and were now in need of “catch up”, the message students received, rightly, was that there was no point in working too hard online. It would all be discounted anyway once we were back in school and much of it was just unsupervised busy-work. Those of us trying to deliver our planned curriculum met with resistance as students simply didn’t believe you were trying to teach them anything meaningful that wouldn’t be repeated once they returned to school.

My warm memories of the previous spring became the sour headache of the present. Everything felt more difficult. It was self-evident every day that very few of my students were actually doing the work we set. Most logged on and because foolish “safeguarding” measures meant we couldn’t see their faces, their blank onscreen initials hid the truth of the online gaming or Discord chats that were their true object of engagement behind the curtain. I’d end the weeks frustrated rather than inspired, as I had been the previous spring and summer. It was a joyless trudge that left me empty instead of fulfilled.

Recovered from Covid and given my first vaccine shot by March, I had my doubts the school would be any less sloppy when the re-opening was announced, but like the September before I had already resigned myself to at least showing some willing. I could always drop tools again later if I still felt unsafe. Happily, a mix of the vaccine, regular lateral flow testing (more questionable “science” we’d bought into wholesale in schools despite so many serious reservations about their being fit for purpose from the medical community), and emerging new variants which made the school keep stringent measures even when they were no longer a legal necessity made the place feel more secure than it had done in the winter. We even managed to get to Easter without any new positive cases in school.

When I first heard that the test for Covid-19 involved sticking a swab down your throat that might make you gag I was more scared of the test than I was of the virus. In December it was the knowledge I’d have to do the swab that worried me as we drove to the test centre, not the possibility of the test returning positive. That nowadays I administer such swabs to my own throat at least twice a week without complaint is a sign of the strangeness of the “new normal”, and how easily acclimatised we can become to anything given sufficient time.

The summer term felt more positive after the peaceful Easter break, at least for the younger students. Their classes began to feel almost normal as we all acclimatised to the Covid-classroom and recognised its benefits from the miserable online winter. Exam age students, however, were not so lucky. Instead of teaching them anything new upon their return in March, we spent months simply giving them exam after exam after exam. Then marking all those exams. Then grading and administrating for the exam boards on the grading. What seemed like we might at least be turning a corner became, instead, contemporary schooling at its ugliest. Examination and pseudo-accountability for the sake of examination and pseudo-accountability. Assessment serving as an obstacle to education instead of its facilitator. Soon even the non-examination classes suffered from a lack of priority and attention. Even then, we were still having to revamp lessons and rethink our approach to things. And soon we started having year groups out again as the Delta variant reared its ugly head just as the government decided it was time for school students to remove their masks.

I think our school only lasted a week before we reinstated the mask rule. Why we ever removed it I don’t know? I’m glad we were quick to restore it while other schools weren’t so smart. It helped stop the spread within school even as families outside of school couldn’t help but bring it in. But it angered me that even here we blindly followed inane rules instead of making informed and scientifically-defensible choices.

Somehow, we crawled to July. The exam paperwork got done. The masks returned, even as testing rates fell and parents tried to avoid the potential for economically damaging self-isolations. The plan for these last few weeks of term was to collapse the timetable and do something fun with our classes. Give them some of the opportunities that Covid had taken from them over the last seventeen months. More rethinking and replanning. Heroic re-time-tabling and all around creative adapting…yet, as the country prepared to come out of lockdown despite Delta cases soaring, across the “fun” three weeks there wasn’t a single year group that wasn’t sent home at least once to self-isolate or a week that passed with out masses of complicated re-planning. We were back online again for much of it, only this time from our empty classrooms. Trying to squeeze out some “fun” from the circumstances despite the return of the void and most of the kids just wanting Summer to be here.

The rule of this year has been contradiction. Don’t plan anything as all plans will be disrupted, but also plan for every eventuality because you will need plan b, c and d. Try to make school as normal as possible for everyone and pretend like nothing’s wrong all the while remembering nothing is normal and everything is wrong. Put on a brave face but also put on a mask so no one can see it. Ensure online provision but provide a catch up because online provision is meaningless. Exams are cancelled but there will still be weeks of exams. Equip yourself with all the technology to do things online instead of in person but don’t use it - just complain how things aren’t as good online as they are in person. The virus is spreading at levels we haven’t seen since January - so see you again in September with no more safety measures in place.

I will be glad of the six week break. I need to get away from the constant crazy and contradiction. This year was far harder than the last one. Stopping in-person teaching in March of 2020 and delivering school online until August was a sensible and sane decision which I could make sense of and do well. September 2020 to July 2021 has been one mess and tragedy after another. I will be glad to see the back of it and hope to never have another year like it.

Unfortunately, our government’s ineptitude and the lack of understanding of how this virus works and how to keep it at bay imposed upon the public they have purposefully kept in the dark suggests, come September, chaos will resume. So I will cherish this holiday because I think anyone involved in education right now is going to need to refuel as much as possible for the shit-show to come.

Ce n'est pas un examen

When the government announced in January that exams in 2021 would be “cancelled” it was clear within minutes that they were not actually cancelled - they were simply going to be outsourced…

When the government announced in January that exams in 2021 would be “cancelled” it was clear within minutes that they were not actually cancelled - they were simply going to be outsourced. Instead of exam boards doing the job they are paid for (a job which, by the way, education would be better without) we teachers would be roped into creating, administering, marking and recording our own assessments. A whole bunch of extra work with no extra compensation - financially or mentally - after an insane year reinventing our entire profession digitally and learning on the job how to translate lesson plans into remote teaching, or rethinking how to physically teach our subjects in the new “Covid-secure” classroom.

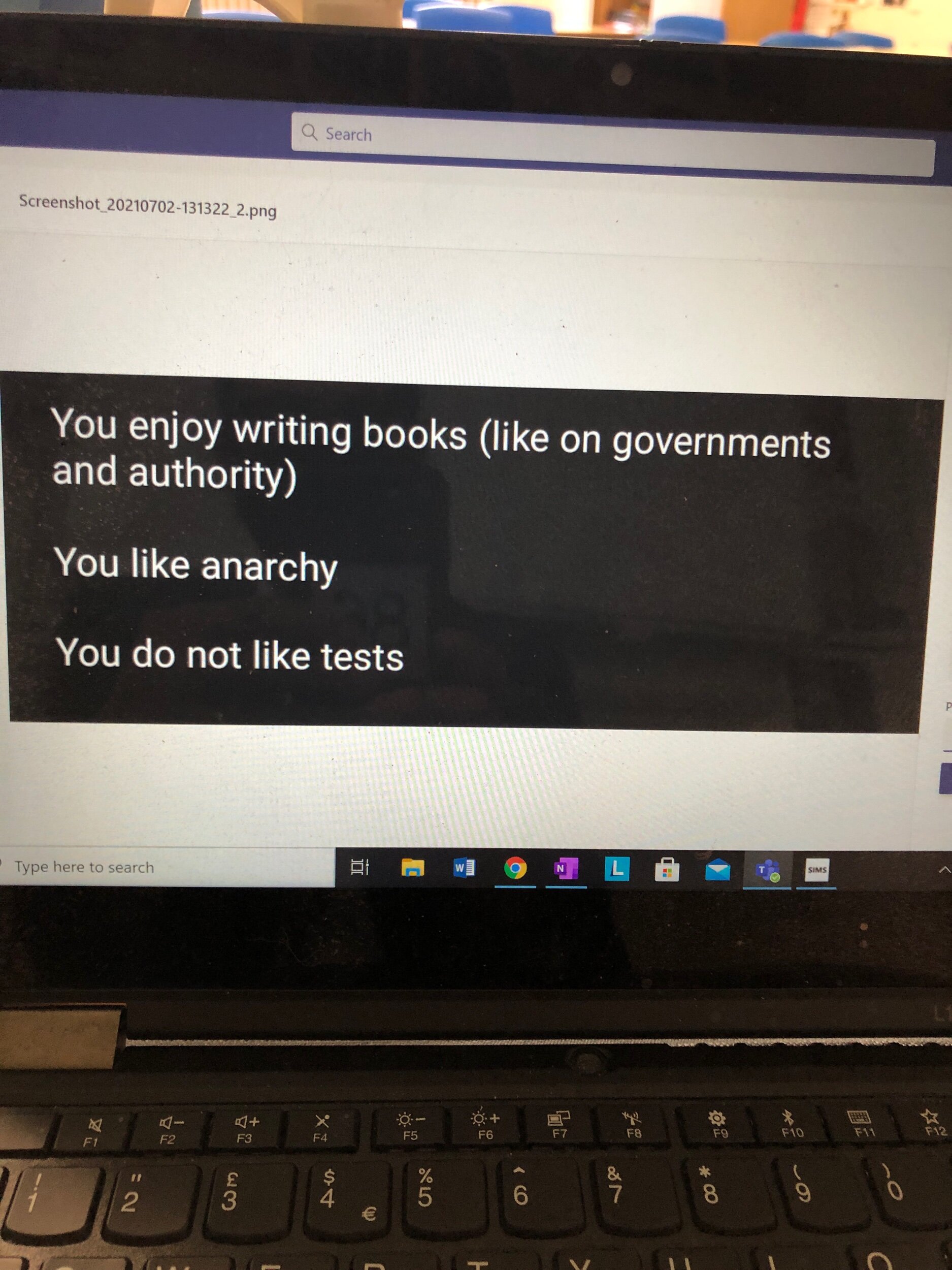

At first though, I was encouraged by the sense of liberation that came with the idea. After all - exams are bullshit. At least they are for my subjects (Religious Studies and Philosophy). By reducing the rich subject areas I teach into easy to regurgitate chunks of rote memorisation we are forced to spend as much time training students how to jump through the relevant hoops of a “4 mark question” compared to a “5 mark question” as we are actually engaging with the course content. This is especially so for philosophy, where the AQA exam really does limit student engagement in actual philosophical thinking to mere repetition of historic ideas (mostly from a stale list of dead, white men). Freed from having to sit those old fashioned exercises in ranking and sorting students for the job market perhaps we could actually do something interesting with their knowledge this year? I imagined verbal assessments - free-ranging discussions that showed their wide range of philosophical thinking? Or perhaps an extended essay on a subject far more interesting than the tripartite view of knowledge? But just as soon as it became clear that exams weren’t really cancelled, it became clear that whatever we would be doing in schools to replace them would merely replicate normal examination. Instead of embracing the potential autonomy and radicalism of throwing out these stale assessments, schools were told to follow the instructions of the exam boards, rely heavily on materials provided by the exam boards, and rigorously “quality assure” the assessments so that they, well, basically mimicked the exams that were no longer taking place.

All thoughts of creativity were tossed aside as we were told to stop teaching students new content and plan how to amass “data” on all the things they had been taught across the last two years of their respective GCSE and A-level courses. Data meaning examined questions we had marked, or could mark, and thereby “support” decisions about final grades.

The weird thing here was that the so-called “cancellation” of exams was because of COVID 19, yet in the guidance from the DfE, and school conversations, very little is discussed about what that means. Basically sitting large cohorts in shared indoor halls for long periods is not tenable, yet in a bid to replicate the “cancelled” exams, schools are packing students in together anyway and giving them internal assessments in their stead. Papers are being passed around, rush-marked to keep up with the increased workload, and very little, if anything, has been said about safely quarantining such papers or how to administer “not exams” in a “Covid-safe” way. And then there’s the whole issue of why, given the obvious likelihood of Covid causing problems for the 2021 exams way back in 2020 when the schools first closed, the exam boards and Ofqual didn’t come up with a digital solution that would have - if they so desperately want our students assessed in this retrograde way - allowed students to safely sit their exams remotely, freeing up already over-crowded schools to be less risky transmission sites of the virus and allowing teachers to give more time to their underserved non-exam classes? Basically - all anyone in secondary education can think about right now is assessment, and specifically how to do it in such a way that all the boxes given to us are ticked so that everyone’s back is covered when the inevitable appeals come in from students who don’t get the grade they hoped for. No one cares about whether the process created to get such work done is “Covid safe”. Covid, if it is mentioned at all, is merely discussed the way actors discuss “Macbeth” in the theatre: a curse whose name should not be spoken lest it tempt a positive test result and the self-isolation of a year group before their assessments are complete.

So since March 8th, when we re-opened the schools, I have not been able to teach either my Year 11 or Year 13 classes anything new, and have instead had to revise content with them and devise multiple examinations to “gather data” on them before we send them home again in a few months time. Even once my “not exams” are finished, there are exams in other subjects they need to do, which means my timetabled lessons with them are either used for those other assessments or time in which they need to be revising for them. I am merely a babysitter and invigilator for my colleagues to gather their data, as they are for me to gather mine. And as the papers come in, my other classes suffer too, being as I have no time to mark their work or think too much about what I’m teaching them. In fact, to help with the workload, thankfully, we have even been given a few days off to do paperwork and get marking done. Which is great and necessary - but means those other classes aren’t getting any teaching and instead of doing anything useful we teachers are just doing the jobs of the exam boards when the job itself is unnecessary.

Because no one needs to be examined in this way. If schools cared about education we would trust our day-to-day interactions with our students as indication of their learning or lack thereof in our subjects. We would not ignore everything but the arbitrarily timed tasks done in silent rows under watchful eyes and without resources; we would credit all the hundreds of instances that their understanding and interest was clearly there in the classroom. And we wouldn’t rank them. A simple “yes they understand” or “no they don’t” would suffice. And the universities would know they could do their chosen subject when they leave us by talking to them rather than waiting for some exalted certificate that shows only on one particular day, in one two hour period, they happened to be quite good at memorisation. The jobs they compete for could have their own in-house ways of determining suitability that would surely make more sense than assuming the random numbers or letters they got in geography, religious studies, maths and biology told them anything of importance about how good a bank manager they’d be.

But we live in a myth. We know the world is unjust, unfair and unfit for purpose and that many live in poverty and many do not have the basic necessities of life. And so the only way we can sleep at night is to tell ourselves that there is a hierarchy. A meritocracy no less! That those who work hard, get good grades, get into good universities and get good jobs and those who don’t fail because they just weren’t good enough. Even as we know that this isn’t true, we tell ourselves that it is because the truth is just too painful: that we have devised a system which requires some to fail so that others may succeed. That success is not based on merit but based on who you know and what advantages and privileges you happen to have.

So we pretend exams are important and their judgements fair. We bend over backwards to ensure our made up, subjective and arbitrary letters and numbers we give are “rigorous” and “meaningful”. We lie to ourselves and we lie to our students.

Like the lie that exams were ever cancelled.

Or the lie that the government cares about our students’ wellbeing.

We lie, lie, lie…and we come up with new ways to categorise and sort our students into a ranked hierarchy of success or failure, condemning some to lives of purposefully designed misery even as we offer others keys to the unfair kingdom.