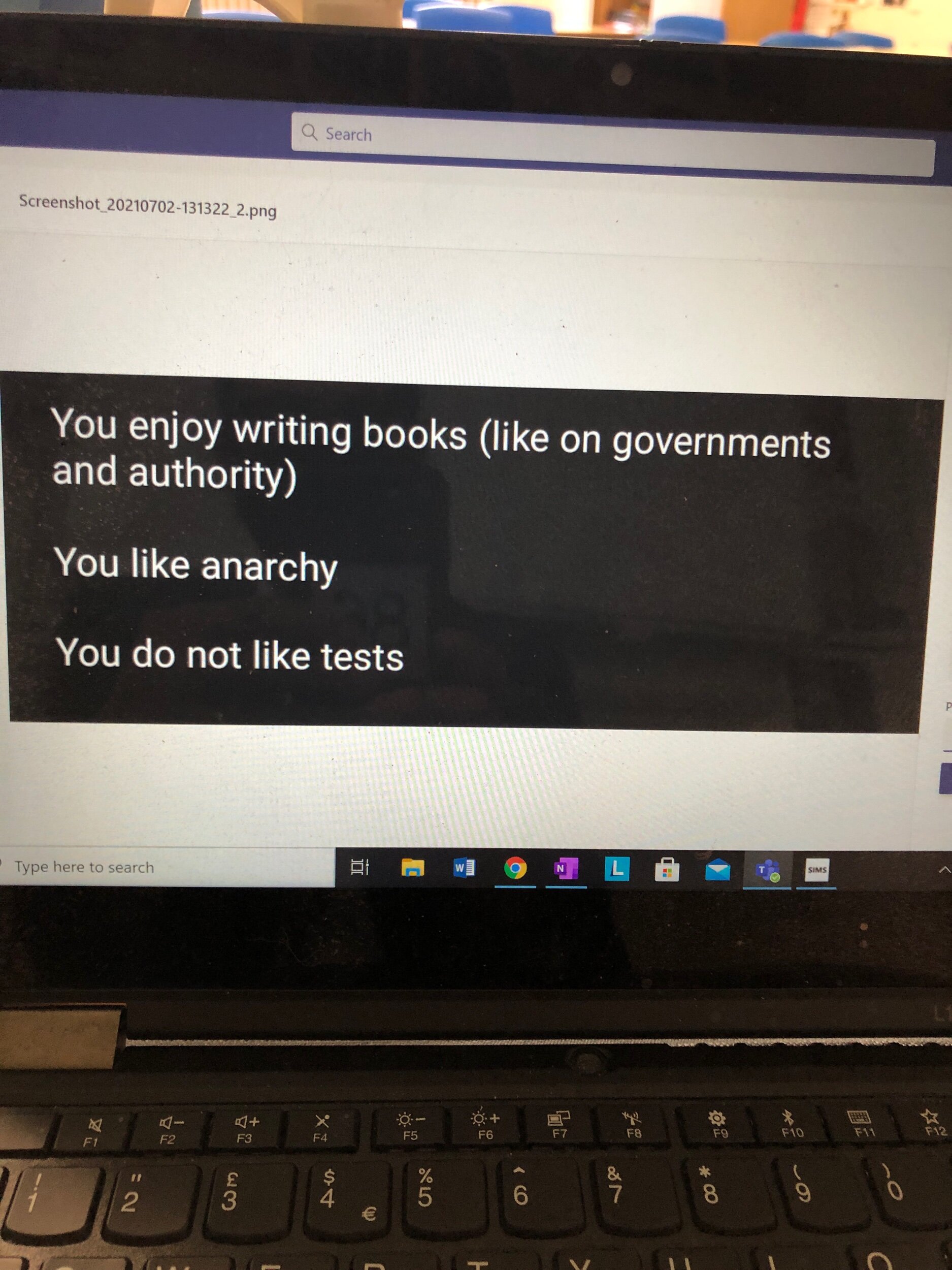

This blog is retired now, but charts some of the final months in the job that I resigned from at the start of ANARCHIST ATHEIST PUNK ROCK TEACHER.

1 in 3 UK teachers are considering leaving the profession in the next five years. I’m currently one of them. This is a blog to reflect on my day to day struggle between personal wellbeing and being a teacher.

Last Day

A lot of thoughts are floating around as I sit in my classroom for the last time on my last day at the school I have worked at for eleven years...

A lot of thoughts are floating around as I sit in my classroom for the last time on my last day at the school I have worked at for eleven years. Leaving is my choice. One I made at the start of the year. But making that choice gave me space for reflection and as the months moved towards the date of my departure what had started as a possible intention to quit the profession entirely evolved into something quite different. A recognition that I still love education even if I don’t necessarily love schools. A recognition that not all schools are the same and that different schools might offer different possibilities. Something closer to the real education many schools often only hint at. And that opportunities to educate outside of the school setting exist too and might be compelling.

But also that this school - the school I am leaving - was one of the better ones. That I had been very lucky doing everything I had done here and that I might not be so lucky ever again.

Also coming to the forefront of my thoughts was a sense of the important need to disentangle teaching philosophy from teaching philosophy as part of religious education and a desire to do more philosophy and less religion going forward. Philosophy as its own thing rather than something smuggled into the cracks of another subject which sometimes threatens to smother it. And certainly there is a desire to focus on teaching in future rather than on leading a department. (Even if my own form of anarchist leadership is fairly hands-off and easy-going - there’s still too much pointless paperwork and stress that gets in the way of the important stuff).

Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly given my initial intention to ditch secondary teaching for academia, there was a recognition that universities are just schools themselves, and often offer just as corrupted a form of education as the institutions which prepare students to attend them. Similar to schools, of course, not all universities are alike. Some places offer something closer to real education than others. But my naive idea to move seamlessly from secondary education into higher education, as if the structural issues with the entire project of formal, highly professionalised, education would magically disappear given freedom away from the rigid National Curriculum in secondary schools, was increasingly exposed as false the more I seriously looked into then possibilities of a life in academia.

I had also, perhaps, underestimated just how hard it would be to get a job in academic philosophy after so many years away from it. My PhD, my book, my journal articles, public talks, weekly philosophy website, glowing references and years of teaching experience have thus far not even got me an interview anywhere I have applied to, let alone a job offer. I began to realise that, whatever happens next, teaching needs to remain a part of my life, philosophy needs to remain a part of it too, and that the academic philosophy work I am doing - the personal research, the writing - can be just as easily subsidised by a part-time secondary teaching gig (or even full-time, without head of department responsibilities) as it could be by a full-time academic position. Bluntly, I’m not prepared to move somewhere across the country and disrupt my wife’s career and our entire life just for a one year temporary contract at a university somewhere. That academics have accepted this practice and made it the norm in higher education employment is a scandal, and sign of deep-rooted problems in the academy. I want to write, think and teach, and will do so wherever that can be achieved.

For now though, with no specific job lined up to go to, I am taking an unpaid sabbatical to focus on the research and try to turn it into a book or some papers. Then, at some point, probably sooner than later, I’ll look to rejoin the teaching profession in some capacity, hopefully as a philosophy teacher somewhere. But having no clear plan of what’s next does make leaving a secure and comfortable job all the more strange and daunting. There’s a disruption to the normal narrative. “Where are you off to?” is a question that should be answered with a firm job offer and clear destination not a shrug of the shoulders and “I don’t know?” The idea of taking a sabbatical to do some research and write some philosophy is a hard one to understand because there is no clear connection to doing that and paying the bills.

Mine is, I admit, a position of privilege. The love and support of a wife willing to be the sole earner for a while. No children we have to feed. A house clear of debt. A willingness to live a more frugal existence for a bit. The freedom to prioritise mental health and personal wellbeing over a career. But it is the fact that these things shouldn’t be privileges that make it so disrupting for people to hear and all the more urgent for radical voices to imagine possible worlds far different from our own: why can’t we all make such decisions? Why isn’t following passions and doing more of what we love and less of what we don’t the norm? Why did we make the world as messed up as we did?

So I sit in the classroom I have occupied for so many years (not the only one I’ve had here. My first for several years was in a different building. The classroom where I learnt my mother was dying. The classroom where I cut my teeth as a professional teacher and figured out who I was and what I wanted to be. But this classroom is the one I have been in the longest and where our RE and Philosophy Department was truly forged.) and I feel very strange. I am eager to leave. Have been waiting to do so since January. Since even before that when the idea first started forming. But there is also so much I will miss. So much of myself I have put into the place. So many people I will be leaving behind.

There is a distinction to be made between institutions and people in those institutions. I am leaving my current job because, as an institution, I believe I have done all that I can do there and that there are now too many things about it as an institution that don’t make me happy or willing to fight anymore for them to change. But that doesn’t mean I won’t miss the people I shall be leaving behind. The colleagues, the students. However, as I have always tried to keep a work/life balance, part of that strategy since day one has been to compartmentalise and keep the two domains separate wherever possible. This has meant over the years keeping colleagues at arm’s length and not being particularly social with them outside of school. Getting on in the staff room, sure. Working together on projects and activities, no problem. But I’m not spending a second of my free-time going to work drinks or after-work gatherings that mean spending extra time in the work domain when I could be off living my real life beyond it. Likewise, if I could get a job done during recess or lunch breaks, I’d rather do it then, at work, where I’m paid to do the work, than take the job home with me where it would encroach on my actual free time. I wasn’t at work to make friends. I have friends outside of work. I was at work because, well, capitalism. I was at work to work.

Eleven years later, this approach has clearly been a mistake. While I have not been totally robotic with my colleagues, I have certainly been aloof, and a level of distance was established that made me feel quite an outsider at times within an otherwise fairly close-knit group of people. The further social distance imposed by Covid over the last few years only amplified that sense of alienation further, especially as I took actions to make myself and my family feel safe that others were no longer taking. Couple that with a lot of fairly outspoken criticism about institutional problems whenever they arose and people can sometimes feel like attacks on systems are attacks on them. Then there’s the high turnover of staff in teaching. If relationships stay only in the staff-room then once that person has left the staff-room the relationship is gone too. The cohort I joined with in 2011 all got along pretty well, but I think I’m the only one left from that group now. The rest of them are just occasional faces in my social media feeds.

I just know that when I leave the school for the last time this afternoon there will be a lot of kind words about what I’ve done for the school, for students, for education, but while a small handful of individual colleagues will be sad to see me go and might even go as far as to call me a “friend”, I am doubtful that many of those left behind will miss me in their day-to-day lives come September. While there were several former students along the way who I kept in touch with as they moved on into their adult lives, and it is perhaps more fitting as an anarchist teacher always looking to raise student voices and be on the side of students against the adult “system” that I end my time at the school with more former students as personal friends than I do former colleagues, I regret not letting more of my colleagues into my “real” life or being more involved in theirs. Separating work and life, while useful for mental health in many respects, also made life at work far less pleasant and humane than it could have been. To leave a place of work after over a decade with the majority of colleagues still only acquaintances instead of actual friends is a fairly bleak realisation that I got something quite spectacularly wrong. While that might not be unexpected from a man who wrote the lyric “those who get it, get it, and those who don’t were never worth the time”, wherever I end up next, I will not make that same mistake again.

That said, there is no doubting the impact my eleven years here has had on people: colleagues and students alike. For every carefully planned lesson I have delivered, there were a million off-the-cuff comments that made far more impact on someone than the learning objectives I had been aiming towards. It’s the interactions between lessons too. The break times, the clubs, the cover lessons, the random chat in the corridor. Even the detentions where you treated someone with kindness and listened to them instead of assuming their guilt. All these things have untold impact. You never know whose lives you have touched and in what way, positive or negative. I hated most of my teachers at school, or was ambivalent about many of them at best. The few I liked loom large in my memories for random acts of kindness or one-off moments of transcendence from the norm. I have always assumed going into this profession that many students will hate me too. That it is important that they do. We all need authority figures to hate and develop a healthy disrespect for. We all need those figures that make us recognise injustice and seek to change the world. And we can’t be all things to all people. I know for some students I was their favourite teacher, and for others their worst, but what I hope is that everyone I taught over the years left my classroom at least feeling something new, thinking something new, and moving forward in their continuing journey to become the person they will end up being in some way for the better. It’s the strangest thing about being a teacher, the ripples your words and actions can have on entire existences in ways you don’t even always know. I’ve actually been surprised this last week as people have said their goodbyes and reminded me of some helpful thing I did here or there for them, especially the amount of help I’ve apparently been to the children of my colleagues. Children who I have never met but have offered advice to through conversations with their parents. Or the randomness of which of my students come up to me and tell me they will miss me. Ones I didn’t even realise liked my lessons or who seemed to actively not enjoy them sad to see me go while the ones I maybe expected to shed a tear left their final lessons with me completely unmoved.

It’s been a weird week to end on. Climate change causing a heatwave on Monday and Tuesday that cut each day in half as the bus company refused to pick students up once the temperature hit the high thirties. All afternoon lessons (some of them due to be my last) cancelled and all of us in summer clothes to deal with the heat rather than the regular uniform or work clothes. Wednesday was our annual Festival of Cultures event - no normal lessons. I taught improv comedy all day (the first time doing any improv since the pandemic closed down our venue in 2020 and we all noticed we didn’t miss it at all) for my last full day of teaching. No philosophy beside the philosophy of “yes, and…”.

Today is a half-day too. Assembly at 11.30 then a staff barbecue to say goodbye to all of us who are leaving. Myself and seven other colleagues. Some retiring, some off to new adventures and other schools. On top of all this, my wife has had COVID since Friday. Given its virulence, I just assumed I would get it too so every day I tested negative and was able to come in felt like a victory of some sort. I was all too aware each day might be my last and I might never even make it to this moment now, sitting here, moments away from everything ending. That I might not get to say my goodbyes because I could wake up each morning to two red lines that would prevent me from coming in without putting everyone else at risk. The personal is the political - my poignant final personal moments set against a backdrop of climate crisis and pandemic.

The other day I was asked by my department colleague for some of the highlights of my time here. I assume he will be giving my goodbye speech this afternoon, as I will be giving his. We are both leaving to pursue a higher calling. Me: philosophy. Him: to lead his church. His departure was a big part of the motivation to leave myself. We have worked so well together since the start and created a perfect “dream team” that the thought of having to start all over with someone else seemed unthinkable. Like that moment in Groundhog Day where Phil tries to recreate his snowball fight and romantic fall with Rita and it just doesn’t feel right the second time. From next year the entire department will be different. Another reason this feels like such a final chapter: it is undoubtedly the end of an era.

So what were my highlights? What kept me here for over a decade?

They all come down to autonomy. The freedom to start an insane Wrestling Club with no actual wrestling involved, using the results of weekly WWE programming as a springboard to students using their imaginations. The freedom to focus more on Philosophy than on Religious Education in my RE department and plan a curriculum I could be proud of as well as amazing enrichment courses and extra-curricular competitions. The freedom to teach improvised comedy alongside my academic subjects. The freedom to take a teacher-led Student Council and make it a truly student-led council instead. The freedom to play my bass guitar and sing angry political punk rock songs to parents, governors and the school leadership as well as students, and to even record and release a punk rock rendition of the stuffy old school song for charity. The freedom to be the sort of anti-leader leader I wanted to be as Head of Department instead of the sort of leader someone might want me to be. The freedom to bring change to the school, from academic policies to the way we approach equality, diversity and inclusion. And, eventually, the freedom not to wear ties. Basically, for eleven years I have been able to follow my instincts, follow my heart, and bring a lot of myself to work each day despite being someone who seems temperamentally oppositional towards much of what a school has to offer. And, in doing so, my greatest highlight has been the freedom to make so many students think. Those who fell in love with philosophy and went on to study it further, and those who didn’t but could never look at the world again without at least questioning some of it. It will forever fill me with joy that the person who steps into my role in September is a former student of mine. Someone whose journey towards being the philosophical teacher they are today is something I played some small part in, and who will be teaching the students of tomorrow in the same classroom in which they themselves were once taught.

Ultimately it’s true what they say: teaching is amazing because it’s always different. Fun and fulfilment can be found in all kinds of different and unexpected places each and every day. The problem for me was that it had stopped being fun and had instead become stale and routine. Same place, year after year. Time to find that fun again elsewhere: another gift of autonomy. The freedom to tap out and leave when I felt it was time to go.

I imagine they’ll strip the walls of my classroom to give the new team a fresh start. I’ve always kept them quite manic - like my own study at home and every childhood, teenage, and young adult bedroom I’ve ever had. Posters everywhere. Collage art. I put up the massive slogan “RELIGION IS NO EXCUSE FOR HOMOPHOBIA” in big bold letters printed on rainbow coloured paper across one wall after too many students used RE lessons, and their faith, as an excuse to say vile things. A statement of fact and also of intent: not in my classroom it won’t be.

I wonder if it will stay? I think of the hours I have spent climbing ladders to fill every available space with thought-provoking images, words, art and ideas. I also notice the gap along the far wall from where, the day before, I took down the large student drawing of Plato’s cave made on massive sugar paper back in my first year at the school. My first A-level class here. A simple exercise: read Plato’s analogy and see if you can accurately draw it to describe its meaning. I kept this particular drawing up because the student who drew it died a few years ago. We named a philosophy prize after him. I couldn’t bear the thought of it just being binned over the summer though, so have taken it home for posterity. Sadly, he’s not the only former student of mine to die. Some have gone in road accidents, some through illness, others have taken their own lives. Whenever I think of those who didn’t make it though, I remember the students who found solace in my classroom. The ones who could have been just another statistic of the crisis in young people’s mental health but who are still here today because they found someone to talk to in me. We all have those students. The ones whose successes can’t be measured by examination results or university acceptances. The ones whose continued existence are success enough and who we continue to worry about long after they’ve left our schools. The ones we are grateful we were there for. In my own case that simple act of putting up a poster - “RELIGION IS NO EXCUSE FOR HOMOPHOBIA” - made all the difference for some students. They are here today, and happy, because I bothered to put up those words on my wall. They were able to be themselves because I was able to be me.

I hope they don’t take them down.

It’s later now. Days later. I am no longer sitting in that classroom on my last day looking at the walls and thinking about the past. I am no longer a teacher. Right now I am nothing. A liminal state between what I was and what I will become. Just a guy in a room typing some words about someone he used to be.

The final assembly was interesting. The reason I decided to record a punk rock version of the stuffy old school song all those years ago was because every summer I would leave for the break with the tune ringing in my ears and imagining it to be better. I particularly loved how the song got quiet and respectful in the third verse, remembering all those former students who had died, before picking up again for a rabble-rousing final verse that was loud and shouty. I always thought it would make a good punk song with big gang vocals at the end and was spurred to finally rework it that way when the Student Council planned to raise money for Cancer Research and I thought it would be a fun way to get donations: a charity single. The last few years though, students have been intentionally messing up the song. Singing it too fast, not being quiet and respectful in that third verse. A real mess. This last time I would hear it would also be the last time for a colleague about to retire after thirty-five years at the school. A special request was made by an Assistant Head, near to retirement himself, that the students sang that third verse correctly, respectfully, and, of course, they did exactly the opposite and sang it louder than they had the first two.

That sort of humour is not to my taste. It’s stupid and it’s cruel. The retiree and the near-retiree were both clearly upset about it and it left a sour taste in the mouths of all the adults in the room. It reminded me of the day a few months ago we took a whole-school photograph and so many students were acting like football hooligans that it got embarrassing. Ugly and abusive chants aimed at teachers and younger students. Delays caused by people unwilling to cooperate for the greater good despite the foul weather. The photographers were clearly unimpressed. I bought a copy of the photo to not only memorialise my final year at the school, but to remember not to always look back through rose-tinted glasses. The picture looks great but it was a freezing cold day with a lot of forced smiles, and that sour taste from the final assembly already brewing in the back of my throat.

They’re not bad kids. It’s not a bad school. But there was a sense of something slipping that needed some greater attention. I’m sure it will get it. Maybe it already is. But I’ve grown weary of giving it mine.

The goodbye barbecue for staff was a nice send-off. Some moving words spoken for each of us leavers, especially for those who were retiring and had given so much to the school. The speech I gave for my colleague was well-received (and well-deserved by him) and the words the Head gave about me got me very emotional. So emotional that I was a bit of a wreck when delivering the speech for my colleague and couldn’t stop shaking for some reason.

As is tradition, they gave us all the expected leaving gift. “Oh good,” I said when given mine, given all my history fighting against wearing the things. “A tie”.

It got a big laugh.

It all felt very surreal though, like I was watching the whole event from outside of myself. I’d felt that way the whole day - like the entire eleven years I’d been at the place was now with me in every room I entered. The years layering on top of each other and events coming and going in my memories: the past encroaching on the present. As I stood inside from the rain, watching people fill their plates with barbecue food I could both smell the onion relish currently in the air and the smell of ancient muddy September mornings spent at this same part of the school - the sports grounds - watching a new cohort of sixth formers embark on ill-fated team-building exercises. I could remember being here too last year, watching kids play bubble football and participate in T’ai Chi. I’d been so inspired by the T’ai Chi sessions I watched that day that I found some local adult classes and have been studying it myself since last September.

I had been worrying all week about what I might say in my goodbye speech.

The goodbye speech had long loomed in my memory. When I first came to work at the school I had started in the last three weeks of July back in 2011 and got my first taste of them then. I will never forget the tirade one incredibly bitter leaver went on, pacing up and down the old dining room and airing every grievance that he had been bottling up for so many years. I knew early doors I did not ever want to give a speech like that, though at times over the years I had feared that maybe I would. Part of my decision to leave was the decision not to end up bitter and twisted like that guy was.

But the goodbye format seemed to change every year and became hard to get a handle on. Sometimes staff leavers spoke in assembly to the students. More often than not they only said their goodbyes after the final bell to the staff in the staffroom. I had always imagined the former - being able to share my feelings with the people I spent the most time with every week and for whom the whole thing was for: the students. But the powers that be had already decided we wouldn’t be talking to students this year. We didn’t even have a whole school goodbye as there were too many of us going to fit it all into a single one. Instead, we had groups of us split up for different mini assemblies across the weeks. Our school captain team gave a speech about each of us and we sat and smiled as everyone clapped. But there was no right of reply. The speech I was given was great, and the student someone who genuinely knew me (even if he did make up a fake anecdote about me quoting Star Wars that never actually happened). The years who got to see it - Years 10 and 12 - were year groups who knew me well and who I had taught the vast majority of. It was nice. But not everyone got that. Some were given speeches by these same students despite them not really having ever taught them, in front of year groups they maybe only knew a handful of. So I guess I was lucky. But it wasn’t the goodbye I had always imagined.

Many years ago, I imagined hiring a clown to come in during the middle of my speech. I have always used clown-horns in the classroom as a way of getting attention in a noisy room. I had a few hanging around from my improv comedy days, but if students asked me where I got them from I would always tell them I killed a clown for them. It got to the point where a whole mythos was born: I had killed a clown for their horn and one day a clown would likely come and kill me for it too. I imagined standing in assembly on my last day and laying out some goodbye platitudes and the door to the hall flying open. A clown slowly walking up to me without speaking as I looked on in fear. “I knew this day would come”, I would say as they brandished a plastic gun at me. When the flag popped out saying “BANG!” I would clutch my heart and fall to the ground, releasing a horn hidden in my jacket pocket and they would quietly stoop down and pick it up before leaving the room as silently as they had arrived. Why not end a career on a crazy bit of performance art?

But there would be no speech to the students, let alone an opportunity for dramatic hijinks. And as the years had progressed I’m not sure if any of them even remembered the weird clown stories I had told them in their younger years. Instead of Pennywise’s majestic floating red ones, in 2022 the bit would have gone down like a lead balloon.

Then I had hit on the idea of an impromptu gig for students. My final “Angry Man With a Bass” show. I had planned to do it for Festival of Cultures. Just put it on during lunchtime and see if anyone came. “Those who get it, get it…” and all that. I would sing some songs, say a few words… But on Monday I tried to change the strings on my acoustic bass guitar for the first time in four years and discovered two of the tuner heads had broken and I couldn’t get replacements to repair it until Thursday.

At least there would still be the staff speech after school though. That was the one I was fretting about when I woke up wide awake at five in the morning on the last day of term. I knew whatever I said would have to be improvised. If I tried writing an actual speech then I would end up writing a book (don’t believe me - remember this epic piece started out as “just a few words”). But I had managed to spend various moments considering some of the ideas I wanted to hit along the way. My gratitude and thanks to the place and the people who’d made the time there so enjoyable, perhaps a few pieces of advice for those I left behind? Share a few stories and shatter the distance caused by my aloofness? I was going to frame it around the four school values we had introduced that year. Diligence, Integrity, Honesty and Kindness. I would use each one as a jumping-off post to build a speech around.

But as it turned out, the worry was all for nothing. The right of reply here, too, was curtailed, only this time by mistake and politeness. The first person given a goodbye speech set the wrong pattern: where in the past the goodbye speech to the leaver was followed by a goodbye speech from them, this person just said thank you and sat down without offering any further reflections. So too did the person that followed. And the person after that. While I did manage to get in my “oh good - a tie” line following the Head’s speech about me, it didn’t seem appropriate to start a whole new speech of my own considering no one else had done so. I just shook his hand and sat down like everyone else had.

I guess that’s why I ended up finishing this weird little reflection I started writing on my phone to distract my whirling mind on the last day: to bring myself the closure I never got from saying goodbye formally to either students or colleagues after eleven years of service?

It’s long enough that I guess I’m glad I didn’t try to say it out loud. People did, after all, have homes to go to and as I shared the goodbyes with seven other leavers, three of whom were retiring and several having had much longer tenures at the school than me, my departure wasn’t that special that it warranted an hour of anyone’s time. Also, even now, with so many thousands of words typed, I have still barely scraped the surface of anything I really wanted to say that day. (A good job I’ve been working on a proper memoir for the last year or so then!) This was more about retaining the memories for myself and processing this strange and life-changing week than about saying goodbye and thank you. But then, I don’t think any speech I could have given would have done the place, and my time there, true justice. Nor would any speech have been able to be honest about all the frustrations I had there without descending into the bitterness I was seeking to avoid, or about the joys I experienced without feeling false in the absence of noting all the frustrations too. That said, having previously given the eulogies to two difficult parents I had very strained, complex, but ultimately loving relationships with, I think I do know the exact tone to set when saying an honest goodbye that is both kind, yet filled with integrity about how things really were. It would have been nice to try for a third.

Instead I have this. An almost reflection. A record, a fragment of something. I don’t quite know what. An attempt to put into words what can’t really be put into words and make sense of the senselessness of mixed and confusing emotions. An appropriately unsatisfactory way of memorialising an inherently unsatisfactory ending because it is so very hard to feel satisfied about something happening which ultimately brings me no satisfaction. An ending I chose, but did not want to ever feel like I had to choose, until I did.

Once the speeches were done I said my individual goodbyes one-on-one, got some goodbyes said to me, and then, fairly quickly, it was all over. I was driving out of the car park no longer a teacher. Certainly not a teacher at that school anymore. A whole chapter of my life come to an end to the soundtrack of a Chris Jericho podcast talking about how he survived a pulmonary embolism in my ears. I called my wife, releasing this was the first summer since I started teaching I wasn’t peeling out of a car park to the sounds of Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out”.

“It happened.” I said. “I did it.”

“Come home,” she said. And I did.

The Beginning of the End

On January 1st I made the leap. I emailed my resignation to my Head….

On January 1st I made the leap.

I emailed my resignation to my Head.

I plan to see out the rest of the academic year at my current job but these will be my last two terms there. I haven’t yet got a new job lined up and have no idea what happens next. I only know for sure that I can’t start another September and still be in that same place. After eleven years it’s become too much of a familiar treadmill and I need something new and challenging for myself. Something intellectually stimulating. Something that thrills me again.

I want to explore my options in academia as well as education. See what’s out there. Find the time to do more academic research than my current position allows me to. I have no idea what my chances are in that completely different job market, but I’m building up a nice little CV of publications and I won’t know until I’ve tried. And if it proves impossible, who knows what a different school might feel like after all these years if I decide to stay in secondary teaching?

My current job, after all, began with similar uncertainty. A late interview. May. For a part-time position. I had almost given up on the idea of getting a job for the new academic year because I was only applying for the ones that felt right to me, and so far that had meant a school I didn’t want to work at, but was near enough to walk to, or this one. I knew the school from others who worked there, and knew specifically that they taught some high level philosophy stuff to the younger years. I’d heard good things and been intrigued. My interview went well. When I started, I thought it would be an interesting detour en route to whatever I ended up doing full-time. By the end of the year I was Head of Department. Eleven years later, here I still am.

So now I return to looking for something new that feels right.

Wish me luck.

On The Last Term

“This has been an interesting term. Eyes open, I got to work day one with a positive attitude: let’s see how I feel about all this…“

This has been an interesting term. Eyes open, I got to work day one with a positive attitude: let’s see how I feel about all this. Even though COVID still ravages on, in schools we have pretended it doesn’t exist. I’ve worn my mask, but most don’t, and in terms of how it is to be teaching it has felt pretty much like any other year. So despite these unusual times, it has been a fairly usual experience of teaching. No classes out for weeks in isolation. My own classroom back. Assemblies. Meetings. The only changes have been positive: a new building open and offering some new resources; a new Head teacher with a new and exciting vision for the school. I have no bad classes either. No group on my timetable which makes my heart sink when I see it, as I have had in some years. If the job of teaching is to be judged then this has been a pretty good term in which to do it: no surprises, no major headaches, just the daily sense of normal in this particular job.

And so, I have judged.

Is this still what I want to do with my life?

Is it fulfilling me intellectually and creatively?

Am I in broad agreement with the aims of the mission of what secondary UK education is in 2021?

Am I making the sort of difference I want to make?

Do I feel this is the best use of my time and talents?

These questions and many more have been bouncing around in my head since September. Every day. Every week. Every month. And as we come to the end of the term and the first long holiday of the academic year approaches, I think it’s time to reflect on what I have observed and felt this last term. How do I feel when I wake up in the morning and put on that suit for school? How do I feel on the commute there, and is it any different from the commute back? When I walk into my classroom, where is my head at? When I leave it at the end of the day, do I feel my time has been well spent? And I guess the really big one: what is the nature of my work? Am I, as a teacher, spending my time teaching, or has the job morphed into something else? Paperwork and accountability - back-covering and Ofsted cowering rather than education and helping young people to develop as thinkers? Are we learning as a profession from things like the lockdown and new research into educational ideas, or is our professionalism merely the nice name we’ve given to obedience and maintaining the status quo? Is the majority of my professional time spent doing things that I believe make me a better educator to my students, or done ticking boxes for bosses?

I have been thinking about all of this over the last term, trying to look at what my job is as objectively as possible, without the negative impact of COVID swaying things as they inevitably did last year and the year before.

It was 2019, I think, when I first stood on a morning duty playground, looking at the students around me playing football and thinking to myself “have I been here too long?” It was my eighth year at the school at that point and I had seen a whole cohort through from Year 7 to their leaving the school in Year 13. Was my work here largely done?

But then the busy-work of the academic year took sway, and then there was a pandemic to deal with.

This September I stood on that same playground and thought the same. Only this year I didn’t lose the thought as the job’s demands took hold, I kept it in the back of my mind as an observing principle. A hypothesis to test and investigate as the new term progressed. And now, at the end of the term, I will spend the holidays when they come next week processing and analysing the data.

NOTES FOR SELF-IMPROVEMENT

Notes for self-improvement…

There’s no such thing as a stupid question is one of the more important principles your best teachers endorsed. Don’t let frustration, speed or inconvenience allow you to undermine that principle in your own classroom.

If teaching is making you unpleasant, terse, jaded, then either quit teaching or do it better. Don’t lose yourself because it’s easier to manage behaviour through fear than through kindness.

Kindness is always better. Always.

Remember what you hated as a student yourself. Don’t do that. Even if there are justifications and rationales for being awful in the classroom, remember what it feels like from a student perspective and what impression will last.

Note down the good things pupils do. Acknowledge them. To yourself. To them. To their families.

No more behaviour or achievement points. They are a false currency.

No more endless detentions. Brief discussions on what went wrong are ok, immediately following the incident. Two mins is more effective than an hour two days later.

No rules - just clear expectations. Flexibly interpreted but consistently reinforced.

End of Term 2021

“Finally…the year that would not die has died...”

Finally…the year that would not die has died.

I remember last September. Having spent an incredibly safe 2020 lockdown mainly in my own garden, venturing out only for the odd walk in a well-distanced National Trust property with my wife, or that one time I got a new tattoo, we had resigned ourselves to re-entering the world despite no change in the danger-levels and faced the new term at peace with the fact of its awfulness. Lessons would have to be delivered differently, the way we engaged with colleagues would be altered - it would all be very weird. But after six months away from school we were as ready as we could be for the weirdness. After all - we’d been sent details of all the safety measures which would apparently protect us from this world-changing virus at work. Hand sanitiser. Masks. Bubbles. It would become the new language of the classroom, rolling easily off our tongues in the weeks and months to come. It would ward off the coronavirus as effectively as any empty spell based on fantasy rather than science.

I knew that too - that it was all doomed to fail. I had written about it extensively in the months before on my Philosophy Unleashed blog and on Twitter. How “bubbles” weren’t bubbles. How we needed good ventilation, not hand sanitiser. How masks needed to be worn in the classroom and not just the corridors - and especially worn by the teacher who was speaking not, perversely, taken off precisely by those projecting their spit and spray out into the air the most (as quickly seemed to become common practice). I found it hard to believe a profession supposedly dedicated to education and learning could buy so completely into these empty appearances of safety instead of basing safety measures on the real science of epidemiology…but I already knew that going in. My eyes were open. I assumed disaster would ensue and was only really surprised it took as long as New Year for the second full lockdown to take place.

September to December was tough. It quickly became apparent even the illusion of safety measures weren’t being followed by everyone at school, or the reasons for them even understood. I felt very isolated and alone for simply asking others to do what was needed to keep us all as safe as possible. Staff and students. There was none of the old camaraderie of the staffroom. I barely spoke to fellow colleagues as my school decided that rather than enforce its own safety measures properly so that all staff would be safe, it would just stick me in a room to work and eat by myself where I couldn’t complain too loudly. Students too, treated the measures with hostility, making every lesson at the beginning a battle of expectations and behaviour instead of a fun learning experience. Meanwhile every lesson had to be revamped for the new Covid-classroom anyway. All our group work, shared resources, etc. had to be thrown out as pupils were sat in straight rows facing the front and unable to interact with each other or us.

In an effort to minimise contact with potentially contaminated surfaces, we tried to get to grips with a “paperless” approach where possible and “enjoyed” all the associated tech difficulties that came with it. It was difficult trying to speak for six period days through a mask so that students could hear and my throat could survive, but we had also lost our classroom spaces and become nomads wandering from room to room across the school, going to our class groups each lesson instead of them coming to us. I felt un-anchored. Adrift. Unhappy.

Then groups suddenly started being pulled out of school to self-isolate for weeks at a time and the hybrid approach of teaching some students in-school and others at home began in full gusto. You never knew what each day would bring.

When that first half-term ended and we reached the holiday that had seemed so impossibly far away in September, where it was finally time to de-stress and feel safe again, we got an email the first Sunday of our break telling us our boss had died. Heart attack. No warning. Friday he was talking to us about strategic planning for the years ahead, Sunday he was dead. Instead of a relaxing and revitalising holiday, I mourned and struggled with a conflicting range of feelings about a man who was both friend and foe. We returned to school and tried to come together in grief at a time when we couldn’t come together. I bristled as protections went out the window so we could do, in school, what no one else in the country was allowed to do at a funeral. The staffroom filled. There were hugs and tears. I stayed away, backing further into my isolation. Alone with my grief.

As cases began to spike, behaviours got sloppier. We were rudderless and doing what was needed to feel ok…but more and more kids had to self-isolate and the rest of the country (just not the schools) shut down in a “circuit breaker” mini-lockdown. Instead of shutting down at school, however, we did a mammoth session of exams. Mocks for the year 11s and 13s. Endless piles of marking. Parents Evenings online. Cold classrooms with windows and doors open despite the frost. Miserable memories of a horrible time.

Getting Covid that Christmas was the icing on the cake. The slow-moving car crash I could see but not stop. The unwanted inevitable. I kept hearing the words of AEW wrestler, Taz, taking a shot at WWE after a Covid outbreak there during the summer while AEW remained clean: “we don’t run a sloppy shop”. Our shop had got way too sloppy…and now I had brought the dreaded plague we had been successfully avoiding all year home with me, ruining Christmas and putting not only my own, but my wife’s life, at risk.

When the lockdown came in January, I was happy. Bluntly, I wasn’t intending on returning until school felt safe again and had written an email explaining my position a day or two before the point became moot and government inaction turned to badly timed action. I had flourished during the previous lockdown, and my department’s online learning provision was excellent. But this one felt far more stressful than before, and not simply because it took weeks for the Covid to leave my system. Instead of the flexibility we’d had before, 2021 online learning foolishly attempted to mimic the school day, so we were staring at screens for hours instead of being able to set appropriate levels of work for the different context. Scratchy eyed days of talking into the void - both of the blank screen staring back at us and the void of expectations wrapped up in the pretence of having too many of them. By starting September with the general consensus that all online learning done in 2020 had been a waste of time, students had suffered “lost learning” and were now in need of “catch up”, the message students received, rightly, was that there was no point in working too hard online. It would all be discounted anyway once we were back in school and much of it was just unsupervised busy-work. Those of us trying to deliver our planned curriculum met with resistance as students simply didn’t believe you were trying to teach them anything meaningful that wouldn’t be repeated once they returned to school.

My warm memories of the previous spring became the sour headache of the present. Everything felt more difficult. It was self-evident every day that very few of my students were actually doing the work we set. Most logged on and because foolish “safeguarding” measures meant we couldn’t see their faces, their blank onscreen initials hid the truth of the online gaming or Discord chats that were their true object of engagement behind the curtain. I’d end the weeks frustrated rather than inspired, as I had been the previous spring and summer. It was a joyless trudge that left me empty instead of fulfilled.

Recovered from Covid and given my first vaccine shot by March, I had my doubts the school would be any less sloppy when the re-opening was announced, but like the September before I had already resigned myself to at least showing some willing. I could always drop tools again later if I still felt unsafe. Happily, a mix of the vaccine, regular lateral flow testing (more questionable “science” we’d bought into wholesale in schools despite so many serious reservations about their being fit for purpose from the medical community), and emerging new variants which made the school keep stringent measures even when they were no longer a legal necessity made the place feel more secure than it had done in the winter. We even managed to get to Easter without any new positive cases in school.

When I first heard that the test for Covid-19 involved sticking a swab down your throat that might make you gag I was more scared of the test than I was of the virus. In December it was the knowledge I’d have to do the swab that worried me as we drove to the test centre, not the possibility of the test returning positive. That nowadays I administer such swabs to my own throat at least twice a week without complaint is a sign of the strangeness of the “new normal”, and how easily acclimatised we can become to anything given sufficient time.

The summer term felt more positive after the peaceful Easter break, at least for the younger students. Their classes began to feel almost normal as we all acclimatised to the Covid-classroom and recognised its benefits from the miserable online winter. Exam age students, however, were not so lucky. Instead of teaching them anything new upon their return in March, we spent months simply giving them exam after exam after exam. Then marking all those exams. Then grading and administrating for the exam boards on the grading. What seemed like we might at least be turning a corner became, instead, contemporary schooling at its ugliest. Examination and pseudo-accountability for the sake of examination and pseudo-accountability. Assessment serving as an obstacle to education instead of its facilitator. Soon even the non-examination classes suffered from a lack of priority and attention. Even then, we were still having to revamp lessons and rethink our approach to things. And soon we started having year groups out again as the Delta variant reared its ugly head just as the government decided it was time for school students to remove their masks.

I think our school only lasted a week before we reinstated the mask rule. Why we ever removed it I don’t know? I’m glad we were quick to restore it while other schools weren’t so smart. It helped stop the spread within school even as families outside of school couldn’t help but bring it in. But it angered me that even here we blindly followed inane rules instead of making informed and scientifically-defensible choices.

Somehow, we crawled to July. The exam paperwork got done. The masks returned, even as testing rates fell and parents tried to avoid the potential for economically damaging self-isolations. The plan for these last few weeks of term was to collapse the timetable and do something fun with our classes. Give them some of the opportunities that Covid had taken from them over the last seventeen months. More rethinking and replanning. Heroic re-time-tabling and all around creative adapting…yet, as the country prepared to come out of lockdown despite Delta cases soaring, across the “fun” three weeks there wasn’t a single year group that wasn’t sent home at least once to self-isolate or a week that passed with out masses of complicated re-planning. We were back online again for much of it, only this time from our empty classrooms. Trying to squeeze out some “fun” from the circumstances despite the return of the void and most of the kids just wanting Summer to be here.

The rule of this year has been contradiction. Don’t plan anything as all plans will be disrupted, but also plan for every eventuality because you will need plan b, c and d. Try to make school as normal as possible for everyone and pretend like nothing’s wrong all the while remembering nothing is normal and everything is wrong. Put on a brave face but also put on a mask so no one can see it. Ensure online provision but provide a catch up because online provision is meaningless. Exams are cancelled but there will still be weeks of exams. Equip yourself with all the technology to do things online instead of in person but don’t use it - just complain how things aren’t as good online as they are in person. The virus is spreading at levels we haven’t seen since January - so see you again in September with no more safety measures in place.

I will be glad of the six week break. I need to get away from the constant crazy and contradiction. This year was far harder than the last one. Stopping in-person teaching in March of 2020 and delivering school online until August was a sensible and sane decision which I could make sense of and do well. September 2020 to July 2021 has been one mess and tragedy after another. I will be glad to see the back of it and hope to never have another year like it.

Unfortunately, our government’s ineptitude and the lack of understanding of how this virus works and how to keep it at bay imposed upon the public they have purposefully kept in the dark suggests, come September, chaos will resume. So I will cherish this holiday because I think anyone involved in education right now is going to need to refuel as much as possible for the shit-show to come.

He’s Hardcore!

There was a horrific fight at work today. Blood everywhere…

There was a horrific fight at work today. Blood everywhere. Myself and a colleague heard an eruption of noise from a classroom next door to us as we worked. Wet break. Too many 14/15 year olds trapped indoors unable to let off steam outside in the downpour. People running down corridors - “there’s been a fight! Come quick!”

And when we arrived, a kid in the corner drenched in his own blood - desks overturned. The blood focusing our attention to the point that we didn’t notice who the specific people were around him. Who the attacker was. Who was responsible. Just checking if the bloody mess that was this student was going to be ok as we cleared the room and got him some air.

He said he was fine and didn’t even know where he was bleeding from.

That’s when the wrestling fan in me kicked in and I looked at his head. The blood wasn’t coming from his skull, but from over his eye. The classic wrestling “hard way” to make someone bleed if blading isn’t an option: a quick, sharp punch to the eyebrow. A big gusher but relatively little damage. Still painful, but hopefully not concussive or a sign of significant damage to the head.

“It’s your eye”, I offered, and as he wiped away the area he looked like something off the cover of Pro Wrestling Illustrated during the heady days of the 1990s - ECW and WWE “Attitude”. Steve Austin at Wrestlemania 13. Any Ric Flair match ever. Mick Foley or Terry Funk.

As further help arrived and the incident began to be dealt with, the kid seemed shaken but, importantly, conscious and not too injured. I messaged him this evening to check if he was alright and was delighted - again, as a wrestling fan - to learn that the hospital had glued his wound together. I used to read about Sabu using crazy glue backstage at the ECW arena to mend his barbed wire gashes before driving to the next show. Now doctors were doing it.

He’s hardcore! He’s hardcore!

A great angle - but hopefully a one-shot deal that won’t lead to a rematch…

How’s The Exam Marking Going?

This is a tweet I composed today but couldn’t be bothered to explain so didn’t end up sending…

This is a tweet I composed today but couldn’t be bothered to explain so didn’t end up sending:

Seriously - one question about the compatibility between the Big Bang and religious teachings keeps showing just how little these 16 year olds seem to know about the evidence and arguments that support the scientific claims, as well as their general lack of understanding of the scientific method. I keep getting versions of “the Big Bang is just a theory, whereas [Insert Scripture X Here] is the infallible word of God”, as well as being told the Big Bang simply “can’t have happened” because “it’s impossible” whereas “we know” God has the power to create the world. The severe lack of consideration for the potential metaphorical and poetic role of scripture in telling the story of creation hints at a whole new generation of future fundamentalists looming on the horizon. And most of these kids have chosen to study at least one science next year for A-level!

And then there’s the question about human rights and religious teachings - would we need human rights laws if everyone just followed religious teachings? Well - a number of my students seem perfectly content to argue horrific versions of “of course [Religion X] doesn’t allow homosexuality but, other than LGBTQ people, everyone would be better off if we all just followed religious teachings” - as if LGBTQ+ people do not matter and can just be completely ignored in the equation. The more depressing students have further defended their person-disregarding thesis on some version of “homosexuality is unnatural anyway and if people followed religious teachings they would just be acting naturally and wouldn’t be homosexual anymore”.

Jesus - and I - wept!

I’m not expecting my students to all be enlightened atheists or LGBTQ+ supporting liberals like me, but I am at least expecting them to, at this stage in their education and maturity, be able to a) accept the reality of scientific consensus and recognise that there are many ways in which people happily reconcile their faith and the words of scripture with the agreed facts of the world and that if they do want to reject the science and argue for the primacy of scripture, taken completely literally, as the basis for their epistemology then they need to recognise the immensity and consequences of that decision and address, and at least attempt to defend, it; and b) recognise that whatever they may personally believe God thinks about the rightness or wrongness of certain sexualities, to deny any group of human beings the full spectrum of their universal human rights is abhorrent and as indefensible as any other such discrimination. Religion, as the walls of my classroom have always declared, is no excuse for homophobia. Even if you personally believe your faith advocates views which could be considered homophobic or prejudiced and you choose to hold those views, that belief does not entitle you to make someone who believes something different than you’s life miserable. And if you think your God will reward you for cruelty and violence inflicted on another human being because of their sexual or gender identity, in my opinion it’s time to start asking yourself how worthy of worship such a deity actually is? (Spoiler alert: if God is something that would be worthy of worship then, guess what - you probably got that nasty belief that They would want you to act with hostility and degradation to LGBTQ+ people utterly wrong, because it’s either completely out of character, or God is not who you say they are at all.)

The sheer omission of any attempt at justifying their disregard for LGBTQ+ people and/or all of known science in their writing is so depressing. Oh well - many, many more papers to go…

Ce n'est pas un examen

When the government announced in January that exams in 2021 would be “cancelled” it was clear within minutes that they were not actually cancelled - they were simply going to be outsourced…

When the government announced in January that exams in 2021 would be “cancelled” it was clear within minutes that they were not actually cancelled - they were simply going to be outsourced. Instead of exam boards doing the job they are paid for (a job which, by the way, education would be better without) we teachers would be roped into creating, administering, marking and recording our own assessments. A whole bunch of extra work with no extra compensation - financially or mentally - after an insane year reinventing our entire profession digitally and learning on the job how to translate lesson plans into remote teaching, or rethinking how to physically teach our subjects in the new “Covid-secure” classroom.

At first though, I was encouraged by the sense of liberation that came with the idea. After all - exams are bullshit. At least they are for my subjects (Religious Studies and Philosophy). By reducing the rich subject areas I teach into easy to regurgitate chunks of rote memorisation we are forced to spend as much time training students how to jump through the relevant hoops of a “4 mark question” compared to a “5 mark question” as we are actually engaging with the course content. This is especially so for philosophy, where the AQA exam really does limit student engagement in actual philosophical thinking to mere repetition of historic ideas (mostly from a stale list of dead, white men). Freed from having to sit those old fashioned exercises in ranking and sorting students for the job market perhaps we could actually do something interesting with their knowledge this year? I imagined verbal assessments - free-ranging discussions that showed their wide range of philosophical thinking? Or perhaps an extended essay on a subject far more interesting than the tripartite view of knowledge? But just as soon as it became clear that exams weren’t really cancelled, it became clear that whatever we would be doing in schools to replace them would merely replicate normal examination. Instead of embracing the potential autonomy and radicalism of throwing out these stale assessments, schools were told to follow the instructions of the exam boards, rely heavily on materials provided by the exam boards, and rigorously “quality assure” the assessments so that they, well, basically mimicked the exams that were no longer taking place.

All thoughts of creativity were tossed aside as we were told to stop teaching students new content and plan how to amass “data” on all the things they had been taught across the last two years of their respective GCSE and A-level courses. Data meaning examined questions we had marked, or could mark, and thereby “support” decisions about final grades.

The weird thing here was that the so-called “cancellation” of exams was because of COVID 19, yet in the guidance from the DfE, and school conversations, very little is discussed about what that means. Basically sitting large cohorts in shared indoor halls for long periods is not tenable, yet in a bid to replicate the “cancelled” exams, schools are packing students in together anyway and giving them internal assessments in their stead. Papers are being passed around, rush-marked to keep up with the increased workload, and very little, if anything, has been said about safely quarantining such papers or how to administer “not exams” in a “Covid-safe” way. And then there’s the whole issue of why, given the obvious likelihood of Covid causing problems for the 2021 exams way back in 2020 when the schools first closed, the exam boards and Ofqual didn’t come up with a digital solution that would have - if they so desperately want our students assessed in this retrograde way - allowed students to safely sit their exams remotely, freeing up already over-crowded schools to be less risky transmission sites of the virus and allowing teachers to give more time to their underserved non-exam classes? Basically - all anyone in secondary education can think about right now is assessment, and specifically how to do it in such a way that all the boxes given to us are ticked so that everyone’s back is covered when the inevitable appeals come in from students who don’t get the grade they hoped for. No one cares about whether the process created to get such work done is “Covid safe”. Covid, if it is mentioned at all, is merely discussed the way actors discuss “Macbeth” in the theatre: a curse whose name should not be spoken lest it tempt a positive test result and the self-isolation of a year group before their assessments are complete.

So since March 8th, when we re-opened the schools, I have not been able to teach either my Year 11 or Year 13 classes anything new, and have instead had to revise content with them and devise multiple examinations to “gather data” on them before we send them home again in a few months time. Even once my “not exams” are finished, there are exams in other subjects they need to do, which means my timetabled lessons with them are either used for those other assessments or time in which they need to be revising for them. I am merely a babysitter and invigilator for my colleagues to gather their data, as they are for me to gather mine. And as the papers come in, my other classes suffer too, being as I have no time to mark their work or think too much about what I’m teaching them. In fact, to help with the workload, thankfully, we have even been given a few days off to do paperwork and get marking done. Which is great and necessary - but means those other classes aren’t getting any teaching and instead of doing anything useful we teachers are just doing the jobs of the exam boards when the job itself is unnecessary.

Because no one needs to be examined in this way. If schools cared about education we would trust our day-to-day interactions with our students as indication of their learning or lack thereof in our subjects. We would not ignore everything but the arbitrarily timed tasks done in silent rows under watchful eyes and without resources; we would credit all the hundreds of instances that their understanding and interest was clearly there in the classroom. And we wouldn’t rank them. A simple “yes they understand” or “no they don’t” would suffice. And the universities would know they could do their chosen subject when they leave us by talking to them rather than waiting for some exalted certificate that shows only on one particular day, in one two hour period, they happened to be quite good at memorisation. The jobs they compete for could have their own in-house ways of determining suitability that would surely make more sense than assuming the random numbers or letters they got in geography, religious studies, maths and biology told them anything of importance about how good a bank manager they’d be.

But we live in a myth. We know the world is unjust, unfair and unfit for purpose and that many live in poverty and many do not have the basic necessities of life. And so the only way we can sleep at night is to tell ourselves that there is a hierarchy. A meritocracy no less! That those who work hard, get good grades, get into good universities and get good jobs and those who don’t fail because they just weren’t good enough. Even as we know that this isn’t true, we tell ourselves that it is because the truth is just too painful: that we have devised a system which requires some to fail so that others may succeed. That success is not based on merit but based on who you know and what advantages and privileges you happen to have.

So we pretend exams are important and their judgements fair. We bend over backwards to ensure our made up, subjective and arbitrary letters and numbers we give are “rigorous” and “meaningful”. We lie to ourselves and we lie to our students.

Like the lie that exams were ever cancelled.

Or the lie that the government cares about our students’ wellbeing.

We lie, lie, lie…and we come up with new ways to categorise and sort our students into a ranked hierarchy of success or failure, condemning some to lives of purposefully designed misery even as we offer others keys to the unfair kingdom.

No Healing For A Broken People

I have been so encouraged over the last year at how much my school has tried to improve its equality, diversity and inclusion. Especially as so much of it has been student-led…

I have been so encouraged over the last year at how much my school has tried to improve its equality, diversity and inclusion. Especially as so much of it has been student-led. Following the murder of George Floyd last year, the anger some of our students felt about what they saw as a lack of comment from the school regarding the brutal assault led to some honest and impactful conversations with the Headteacher and the creation of a Black Lives Matter group which has, this year, morphed into a broader Equality, Diversity and Inclusion committee looking at all aspects of “EDI” across the school. Action from the school’s Student Council, and co-ordination with fellow Councils from across all the schools operated by the same Academy Trust - led to a Trust-wide committee with similar aims. Concurrently and independently, a decision was made to start working towards a Stonewall School Champion award - knowing we are a long way off but deciding to start the work right now; inspired by LGBTQ+ students we know need better support than we are currently offering them but who are already breaking down barriers within the school community.

All of this is really promising, and already behind the scenes a lot is being done. Subject audits, transformations to hiring policies and processes, changes in the way we mark exams, and this afternoon some online CPD sessions on inclusivity and diversity. Soon, we will all be receiving training in unconscious bias too. Working on this stuff has been one of the professional highlights of my year and I can already imagine the difference it has the potential to make to so many lives going forward.

At the same time, however, discussion about diversity remind me just how inherently conservative and identity-oppressing schools - at least schools in the UK - institutionally are. We talk about celebrating diversity and ensuring representation, yet ask our students to subsume their personalities into identical school uniforms, punishing them for adding any embellishments which might allow some self-expression. How can we expect our students to flourish as “themselves” when we police their appearance, their language and even sometimes their hobbies at every turn? Meanwhile we continue to teach the disputed curricula of colonialism and marginalisation which remain embedded in formal exam specifications. Exams do not “celebrate diversity” - they instantiate ranking and hierarchy, sorting difference into success or failure that starts in the classroom and ends in the job market. How inclusive can we really be when it remains our prerogative to deny you entry to the next stage of your education or employment on the basis of your aptitude for arbitrary tests of memorisation and regurgitation? What hope have we got to truly create a more equal, diverse and inclusive world when it remains our professional responsibility to groom our students into becoming a certain kind of citizen: one who is accepting of the unjust norms of an unequal and fundamentally flawed social order and able to navigate their way to success within it; a success which, by necessity within such a system, can only come at the expense of somebody else? Someone likely disadvantaged by the structural inequalities and exclusion that, in their lived diversity, has left them vulnerable to systemic prejudices and discrimination?

If I teach my students to reject the whole damn thing then apparently I do not meet the professional standards expected of a teacher. But as the Black radical, Kehinde Andrews, puts it: “there is no sanctuary within this imperial system; there is no respite, no safe space. We can only ever partially heal when we are constantly living under oppression…There is no healing for a broken people while the system that breaks us is left intact.”

Please Load Paper

The blossom was lovely and the roads were moving smoothly. I was smiling and in a good mood as I neared the school. Sure - I had a morning duty to do up on the courts and a few jobs to complete before teaching started - but what lovely weather to stand around in ensuring the different year group bubbles stayed separated as they kicked their footballs around the playground.

And then I saw the buses…

The sun was shining as I drove into work this morning. My wife and I (we drive in a similar direction for 80% of our respective journeys to our different workplaces, so try to keep up with each other as much as possible on our morning commute) had decided to take a route which passed by some beautiful blossom trees. A nice start to the day even if I did almost witness a hideous crash at a mini-roundabout along the way (luckily a quick swerve from idiot #1 spared the life of idiot #2 who was doing an ill-judged U-turn across the roundabout). The blossom was lovely and the roads were moving smoothly. I was smiling and in a good mood as I neared the school. Sure - I had a morning duty to do up on the courts and a few jobs to complete before teaching started - but what lovely weather to stand around in ensuring the different year group bubbles stayed separated as they kicked their footballs around the playground.

And then I saw the buses. Four or five of them, all backed up along the small single road that leads up to the school gates and the dead-end of parkland beyond. The road parents have been explicitly told since September not to use to drop off their children because of congestion and the lack of a throughway. The road that also contains the staff carpark at one of its three dead ends. The road which every morning is a battle of wills between the buses which need to traverse it, the teachers who require access to their carpark, and the parents who foolishly decide a quick drop-off and three-point turn won’t cause any harm…not to mention the residents who park either side of the already narrow street and have their own lives to get on with independent of the comings and goings of our school.

This morning it was bad. Fifteen minutes of waiting in the subsequent traffic jam bad. By the time I pulled into the car park my smile was long-gone. Instead of getting in early to do all my pre-class jobs, I was already late for duty on the playground.

This is not the first time such a thing has happened. Nor will it be the last.

No problem, I reasoned. My form-room where I would be spending the first hour of the day is right next to the photocopier I would need if, as I feared, the booklets I had needed printed off for today weren’t ready. Which, of course, they weren’t, despite them being put in for copying the week before we broke up for Easter. Stupid of me to trust in the system supposedly put in place to ease our stress and workload - admin tasks like photocopying done by dedicated administrative staff so we teachers can focus on the task of actually teaching - but which, instead of easing stress, only contribute to it by being so completely unreliable. (Not because, I should mention, of any particular failing of the administrative staff but more because the hours they are paid to work do not necessarily correspond to the hours actually required to do the job!)

Also not the first time this has happened (and likely not the last); something so consistently unreliable becomes reliable in its own way, so I had anticipated the lack of resources necessary for my period two lesson and didn’t hesitate in popping the document I needed into the machine - a massive 75 page course booklet - and setting it up to make thirty copies while I went to register my class. The sun was still shining and I had enjoyed the bright warmth on the playground as I waited for the bell to ring and relieve me from ensuring students didn’t injure themselves or kill each other while kicking around their footballs. The resources would be ready when I needed them and I was looking forward to doing some PSHE with my Year 12 students deconstructing whatever the school told them was important to take into account when sitting for an important interview.

“Always wear a suit” said the presentation I had been asked to show them, and I made sure to tell them about a recently successful Cambridge applicant who I had explicitly told not to wear a suit for the interview which gained them a place. “Shake hands and make eye contact” it continued - demonstrating interviews inherited biases towards the neurotypical.

My advice to my students said one thing, the presentation said another, and a few other videos from different sources gave further, conflicting, advice.

“Essentially,” I summed it up for them, “it is a waste of time to base your interview preparation on trying to meet the imagined expectations of your interviewer because, as you have seen, different people are looking for completely different things when they interview a candidate.”

I told them the story of the Headteacher who had told me once that I had interviewed well but wouldn’t be getting the job because I had referred to “kids” at one point instead of “learners” or “children”, and how, at a later interview at another school, the Headteacher there who interviewed me used the word “kids” within the first thirty seconds of our chat and I was hired that same afternoon.

“The only thing you can count on,” I concluded, “is being yourself. If you are yourself, and present the best version of yourself, then if they want you, great, and if they don’t, great too - because it obviously wasn’t a good fit.”

As they watched the first video I went to check my photocopying only to find there was no paper in the photocopier and nothing had actually been printed yet. No problem - I had paper in my classroom as it also functions as our department stock cupboard. I ran back and grabbed a new ream and loaded up the machine. Ten minutes later I went back only to find, once again, a problem. This time, however, it wasn’t mechanical. A colleague stood merrily copying their own resources where mine should be emerging.

“Are my booklets done?” I asked with curiosity, looking around and seeing half a booklet tossed aside, unfinished, and the original document which should have still been in the feeder sat beside it.

“I’m not sure?” they said, looking shifty. “Nothing was printing when I came in. But I’ll be done soon.”

Great.

I came back a few minutes later, re-loaded my document and re-programmed the machine to do the job it should already be well on the way to completing. This time I stayed to make sure it was actually working and was relieved to see the first booklet make its way out of the copier’s mouth. After a bit more discussion about interviews and another video stuck on for my class - this time UCAS propaganda about how best to interview for university - I returned to get my work only to find a second colleague now using my department’s paper to copy their own resources.

I was furious. Can’t this simple task just be done without the constant obstacles?

The anger obviously showed on my face because the colleague assured me they had only paused, not cancelled, my job. I took a breath. OK. No problem. Forget about the paper - it’s all paid for by the same tax-payers anyway. It’s not the first time it’s happened and it won’t be the last - but at least the interruption was brief. The disruption was over swiftly enough and, with the colleague’s printing finished, my delayed copying was finally back underway. By the end of the PSHE lesson I had a complete set of booklets for my period 2 class.